SolveSpace Fundamentals

For most of my CAD I use OpenSCAD, a coding-language–based modeling environment that appeals to my programmer/mathematician brain. But when it gets tedious figuring out how to express visual shapes in code, I turn to SolveSpace instead.¹

I’m still fairly new to SolveSpace, and I like it quite a lot, but I haven’t been fully satisfied by the way tutorials explain the theoretical foundation of how it works. They do have very good tutorials that get you modeling hands-on. This is my attempt to complement those tutorials with a more analytical explanation of the underlying system, as well as a general review of using it.

The Basic Process

SolveSpace is a GUI² CAD program that is based, roughly, around this workflow:

- Sketch 2D shapes in a “workplane”

- Transform those 2D shapes into 3D objects by extruding them linearly, rotationally, or in a helix

- Optionally, duplicate those objects by repeating in a line or rotationally around a point

- Repeat the process to create additional components that you can combine together to create a final model

The heart of SolveSpace, though, is the constraints engine. When you are drawing in 2D or extruding in 3D you define the relationship of elements to each other with constraints. You start by drawing something freehand and then you add constraints to give it precision. Constraints can be things like:

- This line segment is 2 units long

- This arc is 20 degrees

- These line segments are parallel

- This point is at the midpoint of this line segment

- This arc has double the diameter of this circle

SolveSpace “solves” these constraints to produce an exact model that meets those specifications.

Sketch 2D Shapes in a “Workplane”

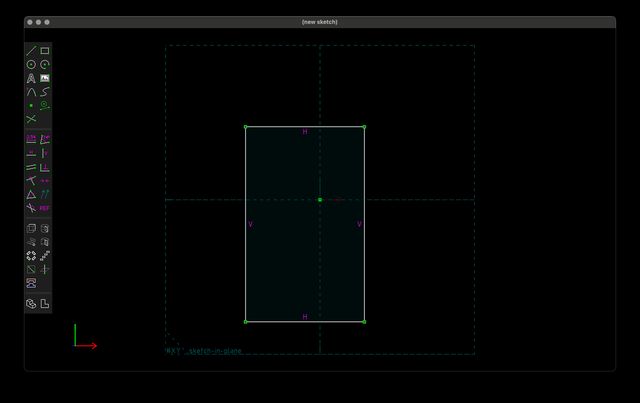

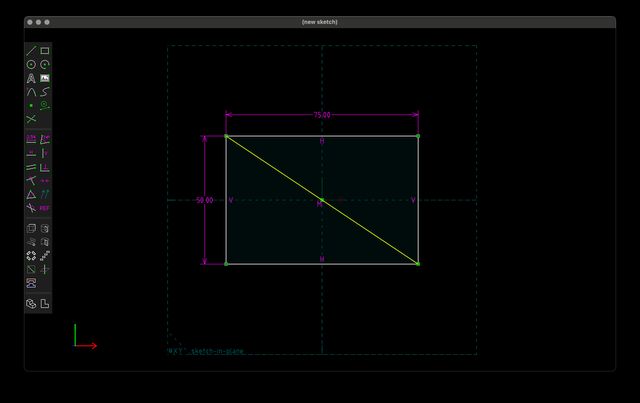

That’s a little abstract, so here’s a concrete example. When you open a new SolveSpace document, it automatically creates an initial workplane for you. SolveSpace has a rectangle drawing tool, but the rectangle drawing tool is really a shortcut for drawing four lines with specific constraints pre-applied:

A rectangle is actually made up of four line segments (represented in white) which each inherently have two points and come with eight automatically adopted constraints (represented in purple). The constraints are:

- Vertical: Represented by the purple

Vs, this constraint ensures that a line segment is vertical (parallel to the Y-axis of the workplane). It’s applied to two sides of the rectangle. - Horizontal: Represented by the purple

Hs, this constraint ensures that a line segment is horizontal (parallel to the X-axis of the workplane). It’s applied to the other two sides of the rectangle. - On Point/Coincident: This is the least obvious constraint. Each line segment naturally has two points, meaning there are actually eight points in this sketch. But each pair of them has the on point constraint applied which specifies that those two points must always be in the same place. These constraints are represented by the small purple dots inside of each green point.

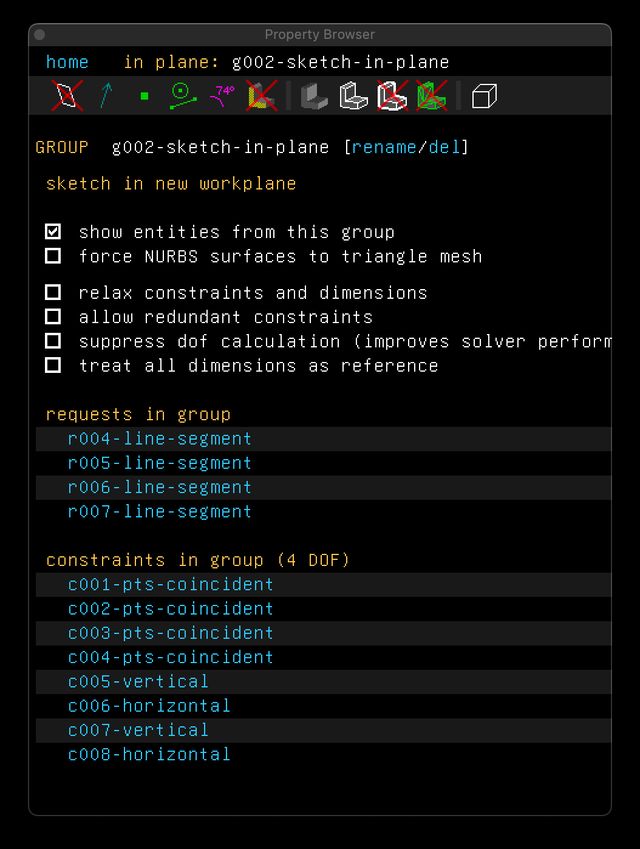

Together these constraints create a rectangle. You can see all the objects in this workplane and all the constraints listed in the property inspector:

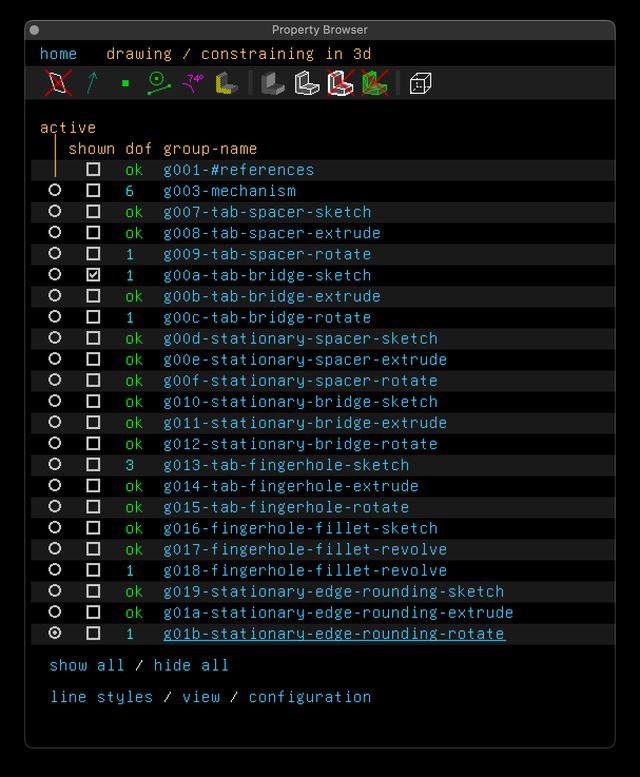

Note that the property inspector refers to this sketch as a “Group.” There’s a number of different “Group” types in SolveSpace that can be thought of as layers or transformations acting on the layers beneath them. A sketch in a workplane is a group. An extrusion is a group. A step repeating (multiplying an object) is a group. Every group has a suite of settings and properties that can be modified in the inspector, as seen here.

As described above you can also see our four line segments (titled “Requests,” I guess because we are requesting that SolveSpace draw them?) and our eight constraints. SolveSpace supports a number of constraint types, but here are the ones I commonly use:

- Distance: Numerically specifies the length of a line segment, the radius of a circle arc, or other similar measurements

- Angle: Numerically specifies the angle between two line segments or “normals” (e.g., axes)

- Horizontal and Vertical: See above

- On Point / Curve / Plane: Can specify that two points are coincident, or that a point must fall on a line, arc, or plane

- Equal Length / Radius / Angle: Specifies that two circles, arcs, angles, or line segments, are equal in magnitude

- Length / Arc Ratio: Similar to “Equal Length” above, but specifies that two measurements have a constant ratio between them (e.g., a line segment is always twice the length of another line segment)

- Length / Arc Difference: Similar to above, but specifies that two measurements have a consistent difference (e.g., a line segment is always two units longer than another line segment)

- At Midpoint: Specifies that a point falls at the exact midpoint of a line segment

- Parallel / Tangent: Specifies that a line segment is parallel to another line segment, or that a line segment is tangent to the endpoint of an arc (if they have coincident endpoints)

- Perpindicular: Just what it says on the tin.

SolveSpace’s interface tries to infer intended constraints as you draw. If you start a line segment on an existing point, for example, it will automatically add an on point constraint to the existing point and the new one. If your line seems to be horizontal, it automatically adds the horizontal constraint. This produces a predictable drawing experience, but most other constraints have to be explicitly added.

You might note, with the eight constraints we have now, we can still move the rectangle around and resize it. SolveSpace lets us know this is the case in the inspector above by saying “4 DOF,” i.e., four degrees of freedom. SolveSpace’s interface gently nudges you toward reducing each group’s DOF to zero, for some good reasons:

- It’s good be able to use drag-and-drop to do your initial sketches, but as your model takes form, you want to specify explicitly what its shape and dimensions are.

- When the constraint solver is forced to resolve (which it is regularly – every time you drag a point to a new location) it attempts to solve in a way that is intuitive, but it doesn’t always get it right. The fewer DOF you have, the less resolving it has to do.

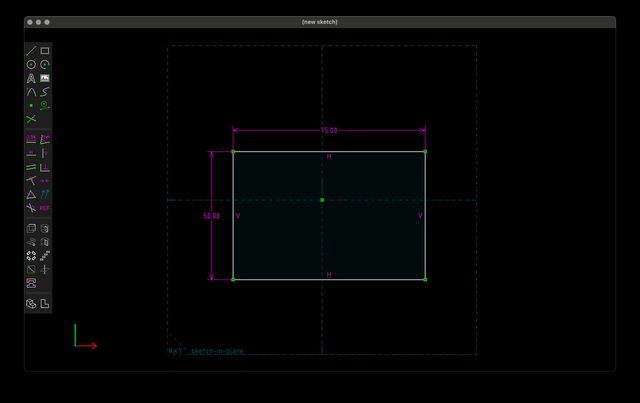

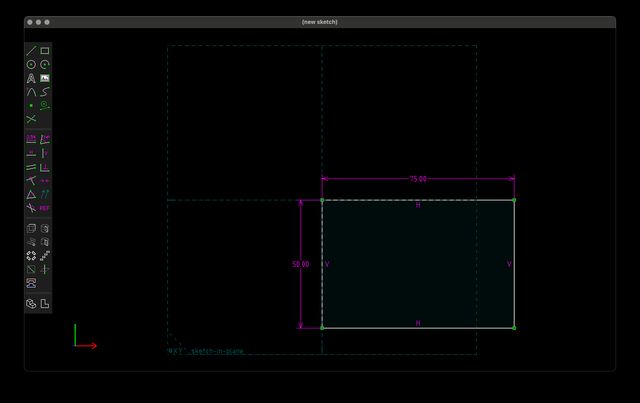

I can reduce the degrees of freedom by constraining our rectangle to some specific dimensions, say, 75 by 50.

At this point the inspector will still report 2 DOF because I can still move the rectangle left/right and up/down. If I want to constrain its position, I can do so relative to the origin point of the workplane (pictured in green at the center). I can do this by adding an on point constraint between the origin and one of the corners:

Or if I want the rectangle centered, it’s a little trickier, but one way to do it is with a construction entity. I can create a line segment going from one corner to the opposite, mark it as a construction entity (meaning it doesn’t physically produce a part of the model, it’s just used for constraint calculations). Then, if I specify that the origin must be the midpoint of the cross-line, the rectangle will be centered (note the M, representing the midpoint constraint):

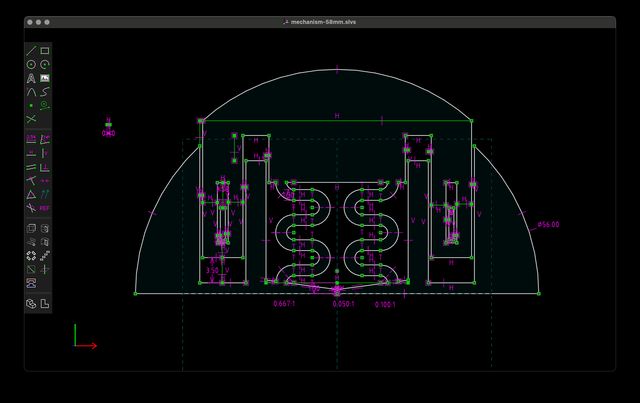

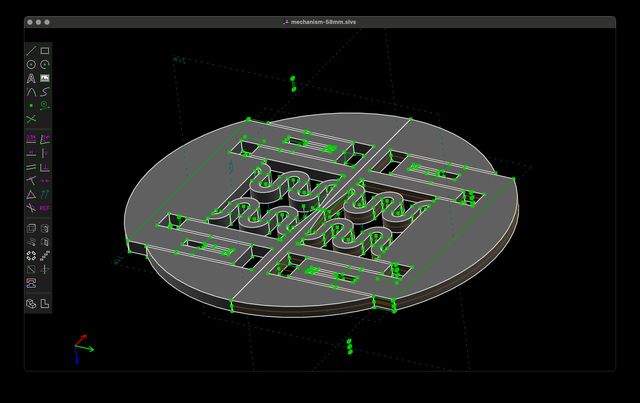

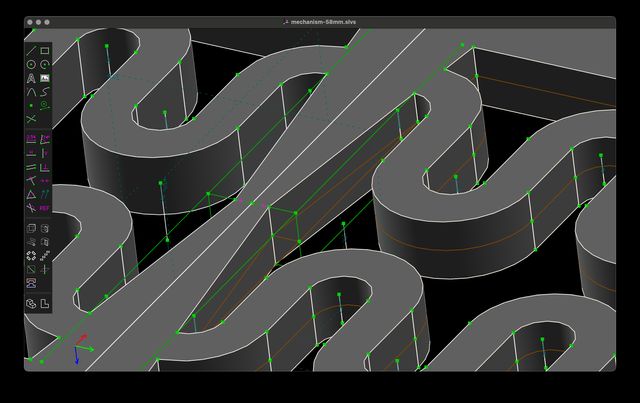

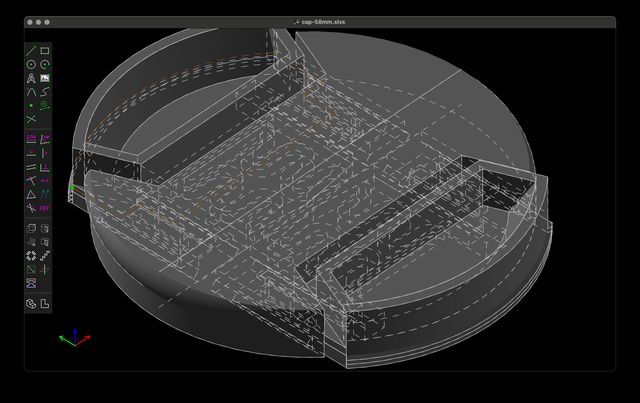

Okay, that’s a lot of detail on just drawing in 2D, but that’s where I spend most of my time in SolveSpace! And using just these basic entities and constraints, you can produce some pretty complex objects. I’m not going to go through creating it step by step, but, as an example to use for the next bit, here’s the initial workplane for a compliant camera lens cap I modeled:

Transform 2D Shapes into 3D Objects

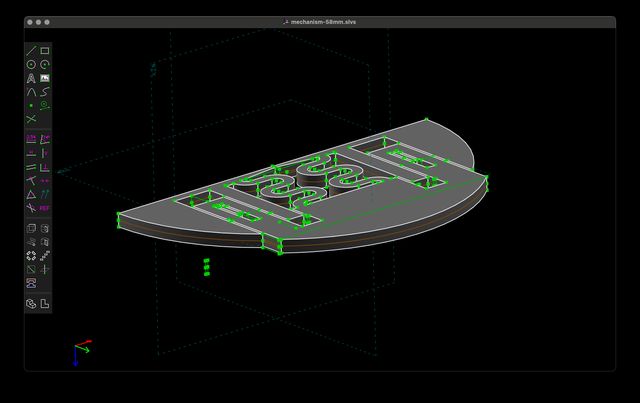

Taking this lens cap mechanism, the next thing I want to do is extrude it into a 3D object. I create a new Extrude group to make it 3D.

Note that this is a two-sided extrusion around the initial workplane (which is on the XY plane) which is why you can also see the outline of the original drawing in the middle of it. An extrusion group naturally has one degree of freedom — how long the extrusion is. I limit this by selecting a vertical edge and setting its length to exactly 2.

My extrusion group now has zero degrees of freedom.

Duplicate Objects

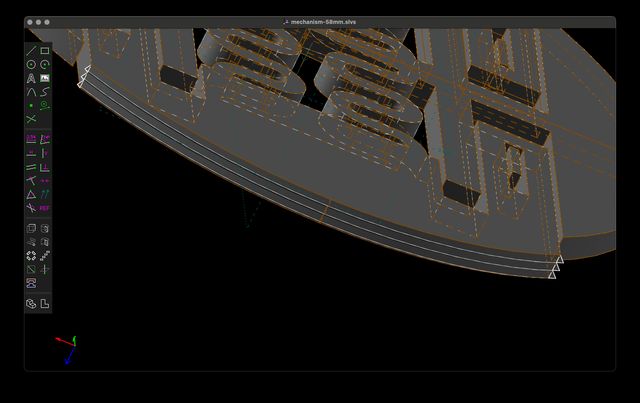

But I’ve only modeled half of the lens cap mechanism. A lens, after all, is not a semicircle. I need to duplicate it across the axis. Unfortunately SolveSpace doesn’t have a reflection group, so instead I’m going to simulate it using the step rotating group, which duplicates the most recent around an axis. A step rotating group needs a point and “normal” to revolve around, so I select the origin and the Z-axis and create a new group. I tell it to repeat only twice (including the inital group).

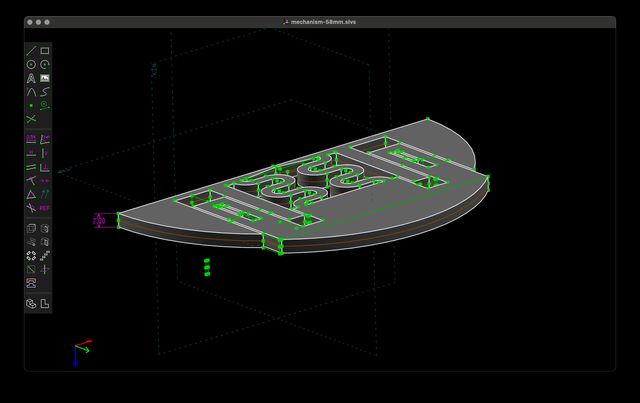

Once again, step rotating groups have one inherent degree of freedom – the angle of rotation. Even though this has produced the rotation I want, by default, I’d feel most comfortable if I formalize in a constraint that it should be 180°. There’s a number of possible ways of doing this, but here’s the one I choose: I select two points that are mirror opposites as well as the ZX plane and apply the symmetric constraint (oops I forgot to mention this one above!) to specify that those two points should be symmetrically positioned across the ZX plane.

Note the small purple arrows in the center indicating the symmetric constraint. Now the step rotating group has zero degrees of freedom.

So, constraints are not limited to when you are sketching in a workplane. You can apply constraints in extrusion groups and repeating groups – and in fact that’s how you define how different 3D components of your model relate to each other. And importantly, constraints are not limited to the group that you’re currently working in. You can apply constraints as relationships across groups. In this case I applied a constraint that is a relationship between a point in the step rotating group and a point in the extrusion group. The entities of any workplane or extrusion that precedes the current group can be referenced.

Combining Components

Making a 2D object and extruding it prismatically is not a very interesting result, no matter how complex the initial 2D object. At this point, to complete the lens cap, I needed to create more components, starting from new workplanes, extruding them into 3D, and then defining how they interacted with the original part.

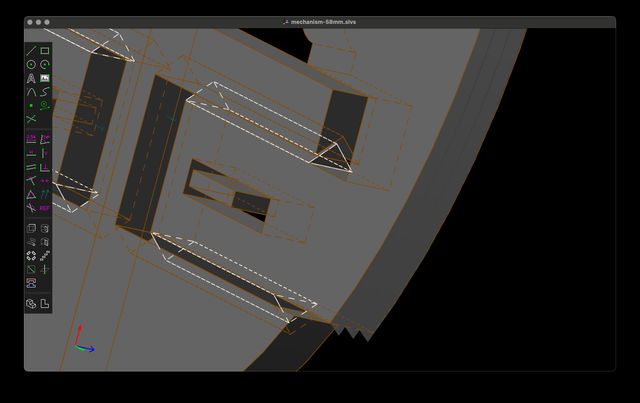

For example, I wanted to create a groove and tongue mechanism to keep the lens cap tabs vertically aligned when pressure is applied to them. I created new workplanes that were along the surfaces I wanted to place these components on, drew triangles, and then extruded them into 3 dimensions – in some cases creating extrusions in assembly mode (e.g., glue these components together) and in some cases difference mode (e.g., subtract this component from the solid model so far):

I enabled stippled occluded lines so you can see with “x-ray” vision the tongue and groove.

For a more complex extrusion, to create the “teeth” that enable the tabs to grip on to the inner ring of a camera lens, I created a workplane perpindicular to the outer arc of the tabs, drew three triangles in a row, and then extruded them using a revolve group around the center of the arc.

You can use these mechanics together to create some pretty complex objects.

The Pros and Cons

Okay, clearly I like SolveSpace. But should you use it? Here’s some pros and cons:

-

Pro: Extremely satisfying if you’re mathematically minded. Thinking in constraints comes easily to me.

-

Con: The interface, as pictured, doesn’t look like anything else on a computer and doesn’t work like anything else on a computer, and can be pretty frustrating to get used to.

-

Pro: It does look like something a 1337 h4xx0r might use, though, which makes me feel pretty cool.

-

Con: It’s really hard to get basic 3D modeling features like fillets and chamfers without a lot of extra work – and in some cases it’s basically impossible. And because of the way SolveSpace’s model works, I’m not sure I expect this to change (though I’d like to see the option, when extruding, to add a chamfered top or bottom).

-

Pro: Tons of keyboard shortcuts that make sketching pretty quick once you get the hang of it.

-

Con: Even basic objects require a lot of complex groups that become pretty challenging to keep track of.

-

Con: Sometimes the solver doesn’t seem to work the way I expect? It will often tell me constraints are impossible to solve that I am pretty sure aren’t (and then I just have to fiddle around dragging and dropping and adding and removing constraints until it works) or, more often, tell me I have redundant constraints³, even if I’m pretty sure I don’t. In some cases it does so when I’ve only added a single constraint to a group!. Fortunately in the redundant constraint case you can toggle a switch on the group to allow redundant constraints, which I do frequently.

-

Con: SolveSpace tries to resolve in ways that are intuitive to the editor, but sometimes it fails. I’ve often tried to pull two points apart only to watch them snap together instead! This can be particularly frustrating if the result is zero-length line segments, which I don’t know how to get rid of besides deleting them and starting over or undoing and hoping it works.

-

Con: Similarly, if you haven’t fully constrained a group, edits in one place can cause unexpected results several groups up. I tried to make multiple versions of the lens cap at different diameters, but I’ve found that if I don’t fully constrain the triangles that make up the tongue-and-groove mechanism, they have a tendency to invert whenever I change the diameter.

-

Con: Undo is pretty buggy and flaky.

-

Pro: Unlike triangular mesh modelers, SolveSpace can produce files that encode arcs in a pure form, leading to smaller files with higher resolution.

-

Con: A lot of the time SolveSpace will produce surface errors trying to combine your multiple groups and you’ll be forced to tick the box that forces triangular meshes instead (“Force NURBS surfaces to triangular mesh”). This has the additional side effect of different errors.

-

Con: If you have a lot of groups, it can get really overwhelming looking at all of them at once.

-

Pro: SolveSpace’s ability to turn group visibility, certain types of entities, and occluded lines on-and-off can be pretty powerful. If I’m working on a workplane that has measurements based on only a couple preceding groups I can just enable those groups.

-

Pro: The constraints system is super powerful.

-

Con: It’s doesn’t generate truly parameterized models, in the sense that you can’t just adjust a few configuration parameters to generate a new coherent model. You can sort of fake it by creating some foundational constraints that represent parameters (e.g., “lens diameter”) but even then you have to have some bulletproof constraints everywhere or deal with the unpredictable side effects of the solver. And you can’t make parameters that are discrete (e.g., “number of teeth”), binary (e.g., “generate finger grip cavity?”), or strings (e.g., “label”).

-

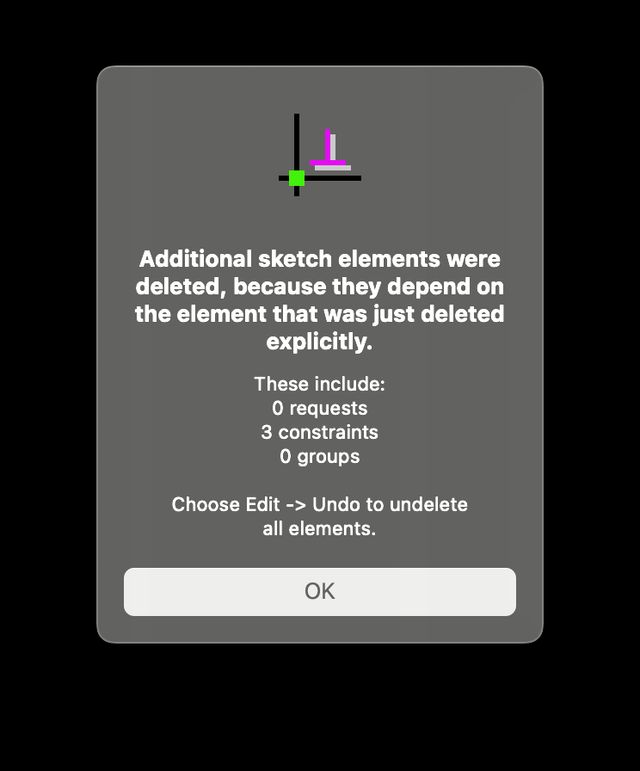

Con: It can be easy to lose track of what entities from earlier layers impact later constraints. SolveSpace tries to warn you when you’re deleting an entity, but those warnings aren’t super informative and it doesn’t provide any warning or way of tracking if you’re just adjusting an entity.

Listen, it’s a great system, it just comes with a lot of caveats.

P.S. The lens cap model is available on Printables.

It should be said that both of these are unusual in the 3D CAD world. They have their adherents, but most modelers use friendlier GUI CAD software like Fusion 360. But both of these are more analytical/mathematical than drawing things freehand and, though they work quite differently, they tickle similar parts of my brain. ↩︎

Graphical User Interface, as opposed to a text-based environment, like OpenSCAD. ↩︎

SolveSpace tries to encourage you to avoid redundant constraints as well as having too many degrees of freedom. ↩︎